Alien Eroticism and Erotic Alienation: Ruth Marsh’s Fruiting Bodies

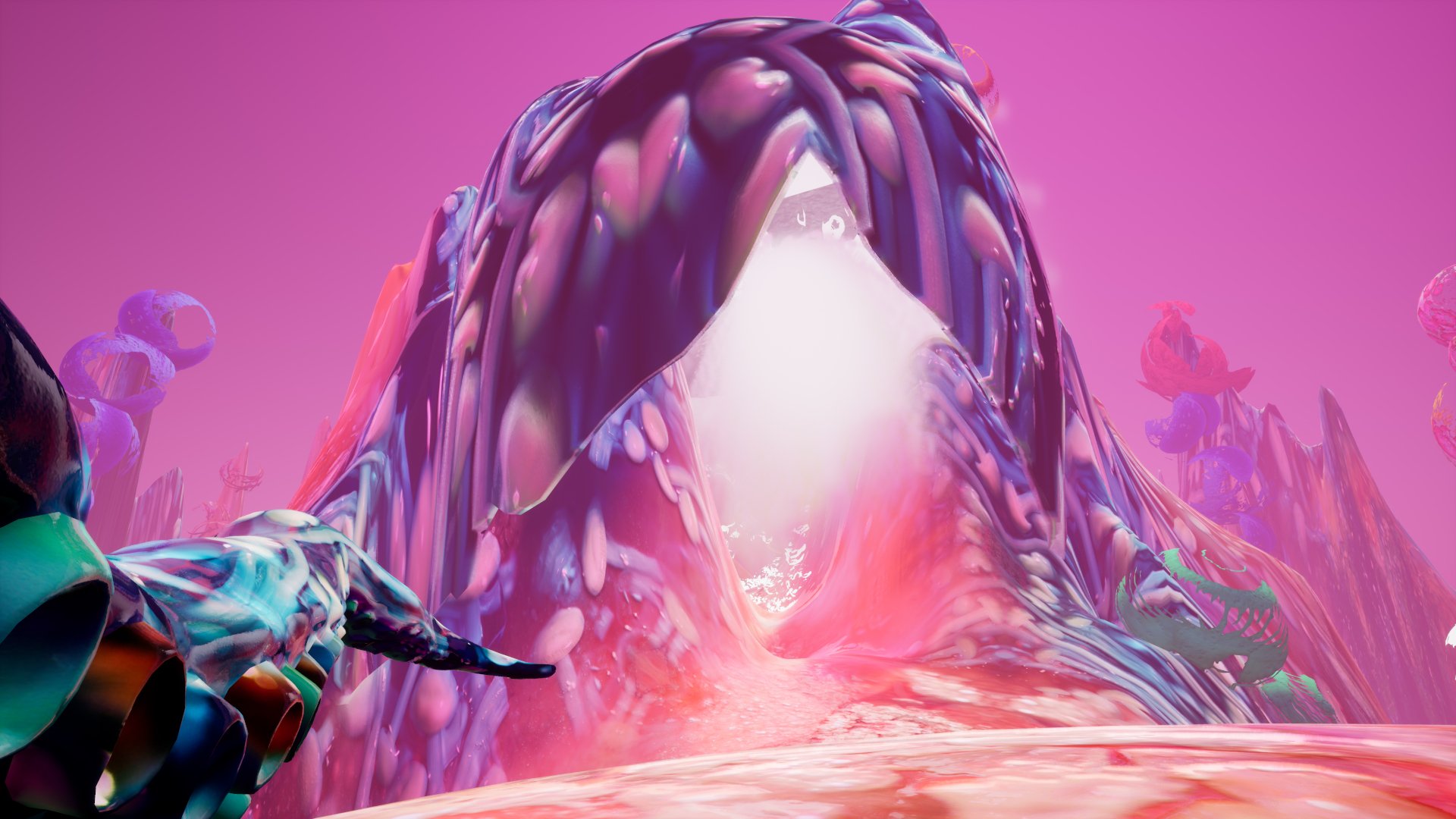

Fig 1. Ruth Marsh, Fruiting Bodies. 2021, Virtual Reality screenshot provided by the artist.

In their VR game Fruiting Bodies, Ruth Marsh has recreated the human body as an alien landscape that players, embodying a tentacled creature named Feltus, are invited to explore. While these landscapes are not always immediately recognizable as human, the titles given to each chapter, such as Chapter 2: Gut Flora, Chapter 3: Treasure Trail, or Chapter 4: Peach Fuzz, provide a framework for understanding, or at least contextualizing, what you are moving through. These titles are often colloquial, and even fantastical, paralleling Marsh’s depiction of the body as bound neither to biological accuracy nor to reality. Instead, Marsh uses a playful referentiality that is more akin to the way a person might relate to their own body as a foreign landscape, a series of biological occurrences that are not fully understood, but lived out regardless.

Part of what makes the body-cum-landscape that Marsh has created so alien is its scale. Our virtual playpen, experienced as a world unto itself, actually transports us to the microscopic. When viewed at this level, devoid of the signifiers that create legible meaning in our day to day lives, our own bodies become foreign and we become alien to ourselves. However, this alien universe is colourful and vibrant, all bright pinks and purples, turquoises and pearlescent whites. Marsh’s vivid palette is inviting, even nostalgic, and makes playful an environment that pulses with life – although not the two or four legged kind. Here, the landscape itself seems to throb and hum, alive and responsive to its alien interloper: the player-as-Feltus uses their tentacles to launch eggs and create musical harmonies with the landscape. Skeletal architecture reverberates in response, and flora open up and sing to us as we approach. High pitched, shallow, and occasionally nasal synthesized sounds contrast with the deep vibrations of hums and moans, felt in the chest. Lo-fi synth music is mixed with recognizable worldly sounds, like water dripping and mouth smacking, that seem to have been passed through a distortion machine, heightening the paradoxical alienation and familiarity of the human body turned video-game-landscape that we explore.

For Marsh, making bodily elements strange happens at the level of process as well as content: the landscapes of Fruiting Bodies are made of domestic objects that have been flattened into the shiny surfaces that we traverse. In order to create this effect, Marsh constructed jello molds that they mixed, covered, and layered with sprinkles, mushrooms, and other kitchen goods, which they then captured using macro photography and re-created in three dimensional virtual reality. These objects become unrecognizable as the everyday items you might encounter in your own home. The familiar is made unfamiliar, both literally and representationally. Home and body undergo a series of transformations that make them into alien worlds.

Marsh’s use of the alien to reorient a relationship to our own bodies also reveals the erotic and autoerotic possibilities of alienation itself. In Chapter 3, we are tasked with a breeding-adjacent exploration: “Feltus, our intrepid betentacled protagonist, must shatter six mushroom-crystal eggs scattered along the Treasure Trail in order to stimulate the landscape to joyfully release its giant, crystalline spores”.[1] However, Marsh is not always so explicitly sexual. They instead draw out the strange pleasure of basic bodily functions and biological activity: growths in the landscape moan and writhe, burst open and come back together. The pleasure offered here is akin to the basic joy of sneezing when you really need to – a release, a biological reaction, an everyday satisfaction. These pleasures are derived not only from the game’s ability to make these embodied processes alien experiences, but from the loss of conscious control over the body wherein we give in and over to need (achoo!). This loss of control over the self, or of the self entirely, is orgasmic.

Marsh’s medium of choice further enhances this loss of the self. Virtual Reality engenders a unique experience of the body because the particular headsets required to play block out the sensation of where and how, in actuality, our bodies are moving through space. This facet of VR gameplay, where the grounding, real-world sensations of self and body are overwritten by the virtual experience into which we are transplanted, is inherent to the medium, and necessary in order to become a player/subject in the game. In Marsh’s world, this is a unique opportunity to replace, or reverse, the place of the human body. As opposed to using replicas of recognizable human forms to navigate this alien world, the only visible manifestation of our virtual point of view is the tentacles we have been given, and which we use to explore a human body as landscape that has been laid out before us.

The tentacle is, in many ways, a loaded symbol, and it is virtually impossible to use it without making reference to its history as a widely recognized erotic object. Marsh understands and uses these intonations and implications. By incorporating the erotic, Marsh allows the player to get caught up in the tension between the familiar and the alien, the erotic and the grotesque, and move between to merge these categories seamlessly.

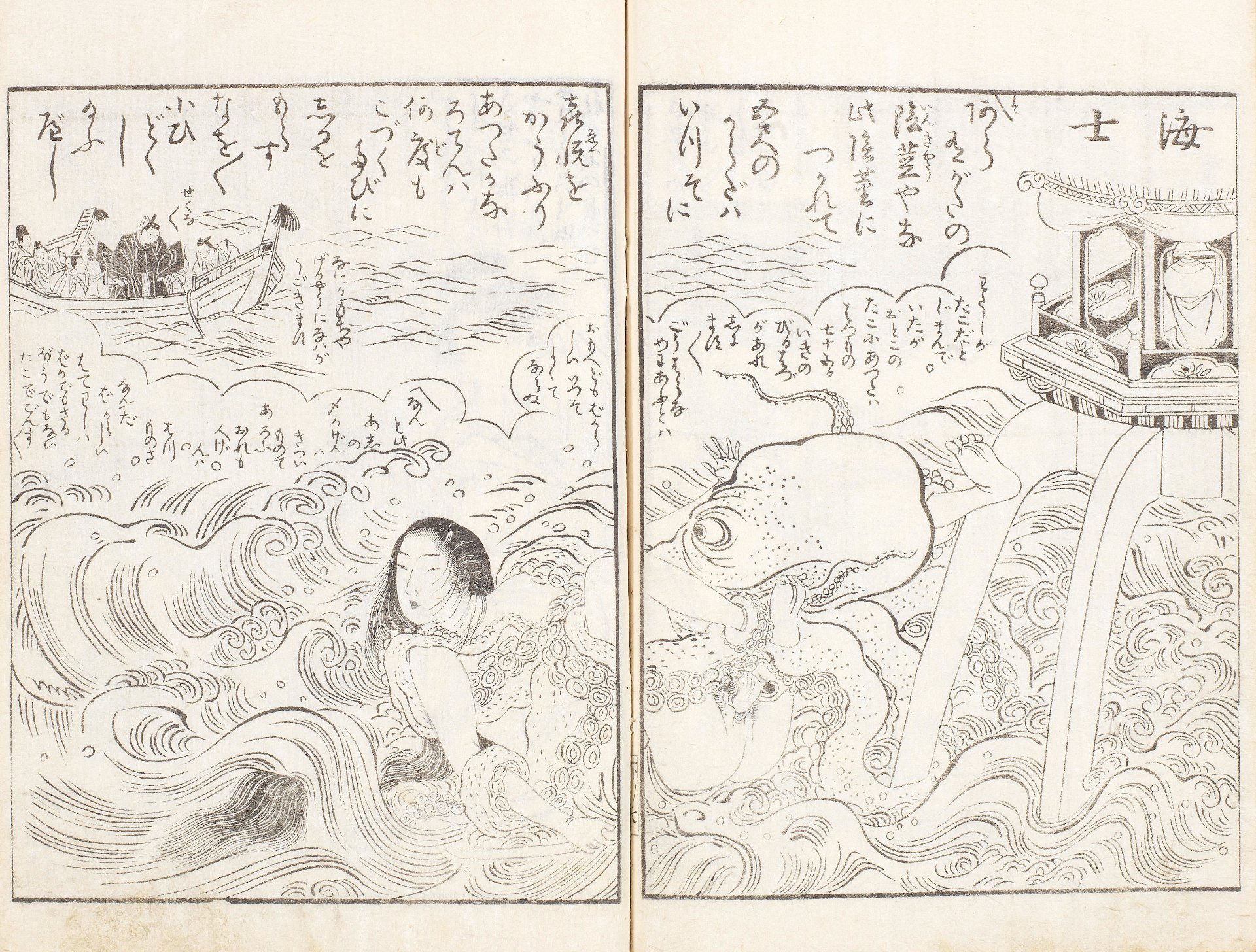

While audiences will likely associate the erotic tentacle with the proliferation of contemporary tentacle porn, the history of the tentacle as sexed dates back much earlier. Images depicting the tentacle as erotic go back to the 1780s, where they first appeared on woodblock prints in Japan such as Kitao Shigemasa’s Programme of Erotic Noh Plays (1781) and Shunsho Katsukawa’s Lust of Many Women on One Thousand Nights (1786). The most famous and most frequently re-created early example of tentacle erotica is an illustration by Katsushika Hokusai, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife (1814).

Fig 2. Katsushika Hokusai, 喜能会之故真通 (Kinoe no Komatsu or Pine Seedlings on the First Rat Day or Old True Sophisticates of the Club of Delightful Skills or The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife). 1814, woodblock print.

Fig 3. Kitao Shigemasa, Programme of Erotic Noh Plays: Octopus and Diver. 1781, woodblock print.

In these early examples, the tentacle is always attached to an earthly (in particular, marine) source - that is, the octopus. Contemporary tentacle porn, on the other hand, understands that the appeal of the octopus’s tentacles stems not only from the phallic nature of the tentacle itself but from the alien-adjacent qualities of the octopus and the sea it inhabits as a kind of alien landscape. The tentacle, free in fantasy from being Earth-bound, is a vehicle for an erotic exploration of the alien that also serves to make the erotic alien.

Contemporary tentacle porn artists also have a more utilitarian explanation for their choice of phallic object: censorship. The tentacle is an image that circumvents regulations in Japan that prohibit the distribution of “obscenity” such as the depiction of genitalia[2]. As Toshio Maeda, credited with the proliferation of contemporary tentacle porn, says, : “this is not a penis; this is just a part of the creature. You know, the creatures, they don't have a gender. A creature is a creature. So it is not obscene – not illegal”[3].

As a genderless phallus, the tentacle is free from human biological and gendered constraints, and can therefore represent penetration unbound from these limitations. Importantly, there can be more than one. Furthermore, the tentacle, while immediately recognizable as a phallic symbol, is also akin to a hand, or a mouth: in the early Japanese woodprints above, it not only penetrates, but caresses and holds and sucks. The erotic power of the tentacle is not just a desire for the phallus, but for the alien, the unknown, the other, the monstrous and the grotesque.

While the West often interprets early images of betentacled sex as depictions of rape, Danielle Talerico claims that Japanese audiences of the Edo period would have understood these as consensual encounters depicting the legend of the female abalone diver, Tamatori, which describes the mutual pleasure of the Octopus and the diver.[4] However, tentacle porn as we know it today is tightly bound to depictions of non-consensual sex. Instead of an octopus whose world the diver has entered, the alien has invaded Earth – and this invasion takes the body as well.

Where the non-consent of much of tentacle porn is an explicit metaphor for alien invasion (and vice versa), in Fruiting Bodies, Marsh turns those associations upside down, offering an alternative approach to alien encounters. They create an aestheticized experience of dominance and submission by using the tentacle as a vehicle for exploring the intermingling of power and pleasure. The player is both dominant and submissive, subject and object, landscape and explorer. Marsh explores what pleasure there is to take in this simultaneous reinforcing and undoing of the boundaries of the self, and further enhances this experience using their medium of choice – by virtue of entering the VR world of the game, we are both literally alienated from our own bodies, and virtually become both alien and alien landscape. However, Marsh finds pleasure in this alienation, and in a game we cannot win, only let ourselves enjoy.

Marsh’s interest in the human body as alien and their exploration of power and pleasure places the erotic in conversation with other aesthetic experiences, namely, the cute and the abject. The cognitive dissonance triggered by our partial recognition of bodily inversion in the game play could elicit a visceral, negative response. What belongs inside of us, now laid bare and vulnerable, produces a breach in the boundary between self and other. This loss of distinction is equivalent to a breakdown in meaning – that is to say that the world of the game is, by definition, abject. Fruiting Bodies, however, feels anything but. Marsh folds the distinctions between disgust, fear, and pleasure into one another, making a playground of what might otherwise be a site of horror and revulsion. Instead, Marsh’s world plays with the limits of what is considered cute – the nostalgic color palette of youthful play, the rounded edges and non-threatening invitation to explore this shiny world – and puts it in relation to the abject, transforming both in the process.

Fig 4. Ruth Marsh, Fruiting Bodies. 2021, Virtual Reality. Screenshot provided by the artist.

Sianne Ngai defines cuteness as the capacity of an object to not only take on lifelike attributes, but because of these attributes, to demand our empathy. Conversely, cuteness seems to epitomize the process of objectification itself: for an object to be cute it must have “some sort of imposed-on mien - that is, that it bears the look of an object unusually responsive to and thus easily shaped or deformed by the subject's feeling or attitude toward it”[5]. The object’s apparent helplessness and passivity inspire both the desire to protect and cuddle, as well as sadism and a desire for mastery over the object.

In Fruiting Bodies, animation is the crux of this affective response: to animate, to grant movement, is to give inanimate objects the effect of having life and therefore the capacity to be empathized with. Marsh’s animation, however, seems erotically charged in its draw towards and responses to the subject/player. This world opens up and takes in the player, not only opening itself up to the possibility of being mastered, but seemingly inviting it. The power dynamics of cuteness intermingle with the eroticism of the game, but here, dominance and submission are less about subject and object than subject and subject.

Where the affective response to cuteness is a conscious, if not controllable, reinforcement of the self as a subject achieved by mastery of one’s objects, Marsh’s problematizes this by using cuteness as a gloss for encountering the abject. The ever-present knowledge that the world being explored is an inversion of the player’s own body and the abjection of this constant revelation undermines the apparent dominance of the player’s position as subject. Marsh’s incorporation of cuteness allows for a more conscious, and pleasurable, encounter with the unconscious breakdown of the subject that abjection responds to.

Julia Kristeva[6] describes how the abject can disturb and dissolve meaning and undo the subject because it forces us to encounter a relationship that precedes object relations: the one with the mother. Birth is the original separation that defines the boundaries of the self. The mother becomes the original abjected object, rejected in order for one to become a subject. Marsh’s use of cuteness reverses this relationship, evoking the sensation that the abject object represented in the game “want[s] us and only us as its mommy”[7]. This allows the player to put themselves in the position of the ultimate subject, the one from whence we came, the mother. We not only take on the role of the alien invader, but are given an opportunity to encounter, as mother figures ourselves, what might otherwise be abject.

This re-entering of the body is a kind of reverse birthing scene – we are invited to explore an erotic re-imagining of our own origins, wherein we take on the role of both the mother, the father, and ourselves, the subject. Our bodies are the landscape, our tentacles are the phallus, and we recreate ourselves as masters of our own making, as figures in control of our own emergence[8]. It’s a reassemblage of ourselves as having ultimate control of our own origins.

However, this reassemblage is simultaneously a breakdown of the boundaries that define and separate us as subjects from objects entirely. To become this ultimate subject, we must regress to a pre-objectal state, a state in which we have no objects and are therefore not subjects at all. In becoming figures in control of our own emergence, masters of our own bodies as worlds, we simultaneously dissolve all of the boundaries of self-definition previously erected. Fruiting Bodies can only create the imagined possibility of a self-made subject by destroying the subject itself entirely. By folding the cute, the abject, and the erotic, into a singular experience, Marsh creates a landscape for the doing and undoing of the subject. We explore, and in doing so, we make ourselves as masters, and take ourselves apart as worlds.

Fig 5. Ruth Marsh, Fruiting Bodies. 2021, Virtual Reality screenshot provided by the artist.

While there is no denying the pleasure derived from the apparent dominance over ourselves and the reinforcement of our positions as subjects, Marsh reveals the equal satisfaction in breaking down the subject, in losing control and dissolving the boundaries of the self – like the scratching of an itch, or the release of a sneeze, a submission to need and a giving up of self-mastery. Where the abject responds to and reveals the impossibility of bridging the contradictions of subjectivity via terror and disgust, in Marsh’s world, the erotic creates the possibility for experiencing pleasure in the simultaneity of self-mastery and self-dissolution, in the creation and destruction of our own subjectivity. Not only that, but Fruiting Bodies turns this process into a playground, a joyful exploration and experience of embodied erotic possibility. Despite being removed from our bodies and from reality, we are wholeheartedly reminded of the unbound potential for pleasure in ourselves.

References

Japanese Penal Code, Article 75. https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en (accessed Dec. 2023).

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Marsh, Ruth. Fruiting Bodies, Iota Institute. Virtual Reality, 2021.

Ngai, Sianne. “The Cuteness of the Avant Garde.” in Our Aesthetic Categories, 53-109. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Talerico, Danielle. "Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints: A Fresh Approach to Hokusai's Diver and Two Octopi", in Impressions, The Journal of the Ukiyo-e Society of America, Vol. 23 (2001).

Fig 1. Ruth Marsh, Fruiting Bodies. 2021, Virtual Reality screenshot provided by the artist.

Fig 4. Ruth Marsh, Fruiting Bodies. 2021, Virtual Reality screenshot provided by the artist.

Fig 5. Ruth Marsh, Fruiting Bodies. 2021, Virtual Reality screenshot provided by the artist.

[1] Iota Institute. “Fruiting Bodies Virtual Reality by Ruth Marsh,” 2021.

[2] Japanese Penal Code Article 175, https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en.

[3] Toshio Maeda. “Toshio Maeda: Hentai Pioneer.” Tokyo Reporter, November 8 2008.

[4] Danielle Talerico, "Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints: A Fresh Approach to Hokusai's Diver and Two Octopi", in Impressions, The Journal of the Ukiyo-e Society of America, Vol. 23 (2001).

[5] Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories pg. 65.

[6] Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection.

[7] Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories pg. 65.

[8] The phallic nature of the tentacle is not only problematized by its capacity to suck and hold as well as penetrate, but in Fruiting Bodies the tentacle shoots eggs, further blurring the difference between semen and ovary, or sperm and egg.

Alien Eroticism and Erotic Alienation: Ruth Marsh’s Fruiting Bodies by Violet Pask is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License